Experience the most vibrant,amazing yet unpredictable strip of land on earth.

Saturday, September 22, 2012

Saturday, August 25, 2012

The Code of Hammurabi (1772 BC)-one of the earliest code of laws discovered. Displayed in the Louvre Museum of Paris, France.

One of the oldest deciphered writings of

significant length, the Code of Hammurabi is the longest surviving legal text

from the Old Babylonian period. Although Hammurabi's Code is not the oldest

code of laws in the world, it is the best preserved legal document from the ancient

Near East. The code was issued by Hammurabi, the 6th King of ancient

Babylon who ruled for 42 years from 1792 to 1750 BC. The almost complete code

survives today on a 7.4 ft tall shining black diorite stele in the shape of a

huge index finger. A total 282 laws, carved in 49 columns and 28 paragraphs in ancient

Akkadian language, the code deals mainly on civil, criminal, and family matters

of the Babylonian society. The stele was

discovered from ancient Susa, Elam (modern Khūzestān in Iran) by French archaeologists

in 1901 and currently on display in the Louvre Museum of Paris, France. Here is

a link to an English translation of the complete Hammurabi Code.

The discovery of the Hammurabi Code is important for

Biblical studies as it supports the authenticity of the Law of Moses. The

similarities between the Code of Hammurabi and the Law of Moses are so much,

some even hypothesize that Hammurabi influenced Moses while writing the Torah. The closest parallel comes

in the common wording of "eye for an eye" and "tooth for a

tooth" (Hammurabi Code 196, 197, 200 and Exodus 21:23-25). Although there

are certainly similarities, there are also many differences. Mosaic Law is based

in the worship of one God and involves spiritual principles, whereas Hammurabi

Code is mainly civil and criminal. The Hammurabi Code written at least three

centuries before Moses (1500-1400 BC) is also an answer for Bible critics who believed

that Moses could not have written the first five books of the Old Testament

because the art of writing was not developed until well after his death.

Monday, July 16, 2012

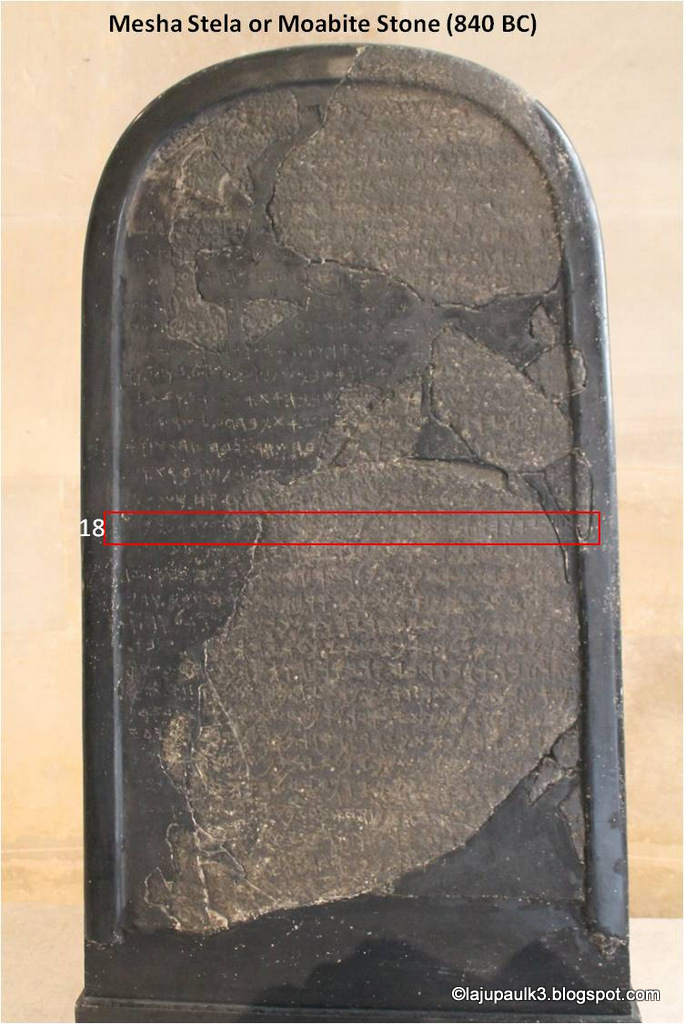

"Mesha Stele" or "Moabite Stone" (9th Century BC), Louvre Museum, Paris. Considered as one of the oldest inscription where the sacred name "Yahweh" (YHWH) is used in written form. The name 'Israel' is mentioned 6 times in this stele from 840 BC.

"The Mesha Stele" or the "Moabite Stone" was by erected by the Biblical King "Mesha", king of Moab, at Dhiban (in modern Jordan) around 840 BC. Scribbled on a three feet tall black basalt rock in Moabite language (very similar to ancient Hebrew), the 34-lined Mesha Stele is one of the longest monumental inscriptions ever found from Israel-Palestine region.

"And Mesha king of Moab was a sheepmaster, and rendered unto the king of Israel an hundred thousand lambs, and an hundred thousand rams, with the wool.But it came to pass, when Ahab was dead, that the king of Moab rebelled against the king of Israel"( 2 Kings 3:4-5).

Mesha stele is an important discovery in the field of Biblical archaeology due to a couple of reasons. It is the first non-biblical text (and one of the oldest too) or inscription found in modern times using “Yahweh” (YHWH, or Jehovah), as a name for the God of Israel. The name “Israel” is mentioned six times on the stele. It also names Israel’s sixth king Omri and refers to his sons as well. Some identify the stele containing the earliest mention of the "House of David". In addition, the stone validates many places mentioned in the Bible.

The stele was discovered in 1868, in Dhiban (biblical Dibon) by the German missionary F.A. Klein.In 1873,the local Bedouins smashed the stone into pieces, assuming that it contained a treasure after they saw the great interest it aroused among Europeans. They broke the stele into several fragments, burned it and poured water on it. How unfortunate it is after surviving nature's harshness for about 2500 years, this historic inscription meets such a tragic fate in greedy human hands.

Luckily, with the help of an impression of the Stone made by a young Frenchman named Charles Clermont-Ganneau before it was broken, archaeologists were able to reconstruct about two-thirds of the texts inscribed on the stone (613 of the estimated 1000 letters). Around 60 fragments were recovered (38 purchased by Clermont-Ganneau himself) and the stele was reconstructed in Paris. Since 1875, it has been displayed in Louvre Museum, paris.

In the 18th line of the inscription appear the Sacred name, "Yahweh" and the word "Israel". Look for the words in the enlarged snap.

Mesha stele is an important discovery in the field of Biblical archaeology due to a couple of reasons. It is the first non-biblical text (and one of the oldest too) or inscription found in modern times using “Yahweh” (YHWH, or Jehovah), as a name for the God of Israel. The name “Israel” is mentioned six times on the stele. It also names Israel’s sixth king Omri and refers to his sons as well. Some identify the stele containing the earliest mention of the "House of David". In addition, the stone validates many places mentioned in the Bible.

The stele was discovered in 1868, in Dhiban (biblical Dibon) by the German missionary F.A. Klein.In 1873,the local Bedouins smashed the stone into pieces, assuming that it contained a treasure after they saw the great interest it aroused among Europeans. They broke the stele into several fragments, burned it and poured water on it. How unfortunate it is after surviving nature's harshness for about 2500 years, this historic inscription meets such a tragic fate in greedy human hands.

Luckily, with the help of an impression of the Stone made by a young Frenchman named Charles Clermont-Ganneau before it was broken, archaeologists were able to reconstruct about two-thirds of the texts inscribed on the stone (613 of the estimated 1000 letters). Around 60 fragments were recovered (38 purchased by Clermont-Ganneau himself) and the stele was reconstructed in Paris. Since 1875, it has been displayed in Louvre Museum, paris.

In the 18th line of the inscription appear the Sacred name, "Yahweh" and the word "Israel". Look for the words in the enlarged snap.

Saturday, June 16, 2012

Friday, May 18, 2012

Saturday, April 21, 2012

Sunday, April 1, 2012

PALM SUNDAY-Triumphal entry of Jesus from Beth Phage to Jerusalem.

And they brought the colt to Jesus, and cast their garments on him; and he sat upon him. And many spread their garments in the way: and others cut down branches off the trees, and strawed [them] in the way. And they that went before, and they that followed, cried, saying, Hosanna; Blessed [is] he that cometh in the name of the Lord: Blessed [be] the kingdom of our father David, that cometh in the name of the Lord: Hosanna in the highest (Mark 11:7-10).

Fresco from the Catholic Church at Beth Phage

The Crusader Stone marks the spot where Jesus' journey began.

(Photos from blog archives, November-2009)Saturday, March 31, 2012

'Convent of the Olive Tree’ or 'Monastery of Holy Archangels’: Armenian Quarter, Jerusalem. The traditional (Armenian) site for the house of Annas, who judged Jesus (John 18: 13: Mark 15:15). The venue is opened for the tourists (non-Armenians) only once in a year at the time of Good Friday.

The ‘Armenian Quarter’ inside the Old City of Jerusalem is relatively less explored, in large part due to restrictions imposed on non-Armenians. One such venue is a medieval convent, which reputedly holds a few relics associated with the passion of Christ. Known as ‘the Convent of the Olive Tree’ or ‘Deir-el-Zeituneh’ or ‘the Monastery of Holy Archangels’, the site according to Armenian traditions is the house of Annas who was involved in the trial of Jesus (John 18: 13: Mark 15:15). Another tradition is that the convent stands on the threshing floor of ‘Araunah the Jebusite,’ where David saw the angel of the God standing between heaven and earth, with a naked sword in his hand stretched out against Jerusalem (2 Samuel 24:16-17; I Chronicles 21:15-16). The foundation of the convent was laid by Queen Helen in 4th century AD and remained unknown to non-Armenians until 7th century. It was renovated in the year 1286 by the Armenian King Levon III. Armenians also have the ‘House of Caiaphas,’ (the High Priest who judged Christ), outside the Zion Gate, known as the ‘Holy Savior Monastery’.

The ‘Convent of the Olive Tree,’ is difficult to access and the door at the entrance will be seen closed most of the times. Main entrance to the convent is deep inside the Armenian Quarter, south-east of the St. James Cathedral and positioned at the end of a typical cobbled street of the Old City of Jerusalem. There is also an entrance from the Armenian Museum, which is also blocked to non- Armenians. I was told by the officials at the St. James Cathedral that special permission needs to be arranged to enter the monastery compound as it was opened for the public only once in a year at the time of Good Friday. The only other option is to seek the help of an Armenian guide. I had tried a couple of times to access the compound, but didn’t succeed until I met George an Armenian who runs a shop near Zion Gate. While we bought some Armenian pottery and ceramics, I had a casual discussion with George about their ancient and unique community living inside Jerusalem. I shared my wish with him to see the sacred olive tree inside the convent and asked if he could help us. He was not only kind to lead us to the tree but also went out of the way to leave the shop to accompany us. With an Armenian on our side, the gates were opened and we were let in without any restriction. The following photographs are not possible without George’s helping hand and generosity.

Armenian Ceramic

What to see

Inside the convent is a chapel associated with the flagellation of Christ and a prison where Jesus is said to be held before the judgment under Annas. Another interesting artifact in the convent is a beautifully carved wooden door dated to 1649. In the compound of the monastery lie two unique relics:

Sacred olive tree: believed to be the tree to which Christ was fastened during his trial under Annas. On Good Friday, special ceremonies are held at the tree. The parapet surrounding the tree has many khatchkars-medieval Armenian pilgrim crosses carved on stones. “When the Lord was brought to the presence of the high priest Annas for trial, he was busy with another trial, so they tied Christ to the nearby olive tree and then imprisoned Him. This olive tree has been sacred ever since the earliest Christian centuries and has been the object of reverence for pilgrims. Special care is taken of the tree and new shoots grow from its roots. Archbishop Malachia Ormanyan relates that on the evening of Good Friday, the faithful come to this place and a special ceremony is held there. The fruits of the tree are gathered while spiritual songs and hymns are sung and with the stone of the fruit (olive pits) rosaries are prepared which are spread by the pilgrims everywhere (Armenian Jerusalem, 1931, p. 128). The fruits and stones of this tree are miraculous. Miracles are told related to barren women and those suffering from high fever” (Texts from the Armenian Patriarchate site here).

The Hosanna Stone: a column with cracks resembling the mouth of a human being. According to Armenian traditions, the cracks emerged in the stone when Pharisees asked the disciples to stop shouting Hosanna to Jesus at his triumphant entry to Jerusalem during ‘Palm Sunday’. The stone has been linked with Jesus’ answer given to the Pharisees: “And he answered and said unto them, I tell you that, if these should hold their peace, the stones would immediately cry out (Luke 19: 40).” Another legend is that the cavity was made by Jesus’ elbow as his body jerked at the pain of the first lash. Father Jerome Murphy O’ Connor has written about this unique column in ‘The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide’ (p. 73) as, “Built into its outer wall is a relic that immediately arouses suspicion but which no one can ever prove false”. Unfortunately, I was not aware about this stone at the time of my visit and missed the rare opportunity to photograph.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)